How One Man's Crusade Changed Our Lives

This article, by former Toronto Star publisher and Torstar chairman Beland Honderich, appeared on the front page of the Toronto Star Dec. 13, 1999. Beland Honderich died in 2005.

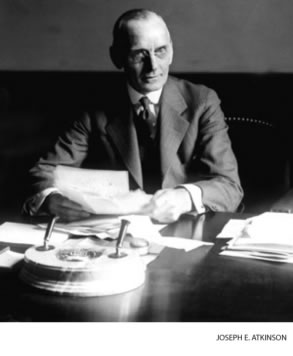

One hundred years ago today a young journalist with a burning social conscience arrived at the Adelaide St. offices of The Evening Star - soon to become The Toronto Star - with the dream of publishing Canada's first mass circulation newspaper.

His arrival attracted little attention. The struggling Evening Star, founded by striking printers in 1892, was the city's smallest newspaper. With only 7,000 subscribers, it trailed behind the city's five other papers - The World, Mail and Empire, Globe, The News and Toronto's dominant afternoon paper, The Telegram.

If the challenge before him was daunting, 34-year-old Joseph E. Atkinson saw it as an opportunity to test his skills and preach his social gospel.

Newspapers then tended to be serious or popular. As he said many years later, he thought "it would be possible to develop a newspaper that would be soundly popular in its appeal and at the same time find ample room for the presentation of the serious interests of human life."

How well he succeeded is a matter of public record. Mr. Atkinson's tiny Star went on to became the largest and most successful newspaper in Canada. And his social conscience left his imprint on much of the social legislation that today makes life tolerable for millions of Canadians.

Mr. Atkinson, by his own admission, was a "tireless, unremitting propagandist" for social and economic justice. He was a leader in the struggle for sickness and unemployment insurance, old age pensions, mother's allowance and much more.

His vision of a Canada in 1899 as a strong independent nation capable of governing itself helped to shape the country's future. So did his strong support, often in the face of angry criticism, of workers' right to organize, bargain collectively, and strike if necessary to improve their wages.

When Mr. Atkinson died in l948, the then editor of Saturday Night, B.K. Sandwell, summed up his contribution to Canada in these words: "He probably exerted more influence on the course of history than anyone else in Canada except for a few top political leaders."

For a man who experienced poverty as a child and had little formal education, Mr. Atkinson's achievements were truly remarkable.

He was 6 months old when his father was killed by a train, leaving his mother in dire need. To feed her family of eight children, she moved to the nearby village of Newcastle, Ont., and took in boarders.

Tragedy struck again when his mother died. He left school at age 12 to work in a woollen mill. A few weeks later the mill burned down and he was left without a job, an experience he never forgot.

"No one can escape his beginnings," he would say, "and I despise a man who is untrue to them."

Religion played an important part in his life. His mother was caught up in the fellowship of the Methodist Church, which soon would be advocating radical change in the capitalist system. Later, in defending himself against business criticism, he would say the reforms he advocated were not as radical as those proposed by the church.

After working as a post office clerk for several years, Mr. Atkinson found employment at a weekly newspaper in Port Hope. There he met a kindly publisher who taught him how to write and sell ads and aroused his interest in public affairs. He began to read biographies. When he learned that Sir Leonard Tilley, one of the Fathers of Confederation, was once a humble clerk like himself, his ambition soared. He went on to read the 18th century reformers - Tolstoy, Henry George, John Stuart Mill and John Ruskin. His reading broadened his knowledge and helped to form his social character.

He was attracted to Toronto at age 22 by an advertisement for a reporter at The World. Later he switched to The Globe. There he became the paper's Ottawa parliamentary correspondent, where he earned the respect of Sir Wilfrid Laurier - and an invitation to come to The Star.

Laurier's Toronto friends, including Timothy Eaton, sensed the need for an afternoon newspaper that would support the prime minister. They purchased The Evening Star and hired Mr. Atkinson at a salary of $5,000 - $3,000 in cash and $2,000 in shares. As the years progressed, he acquired more and more shares until he controlled the company.

Toronto in 1899 was a crowded city of 200,000, stretching from the waterfront to the Canadian Pacific Railway station on Yonge St., west to High Park and east to Greenwood Ave. With newcomers flocking to the city, housing was scarce. Already new communities were springing up around the suburbs.

In many respects, the city was a study in contrasts - stately homes along Jarvis St. with all the amenities of life; crowded slums downtown where life was harsh and cruel. Laissez-faire capitalism dominated business life. Workers were expected to provide for themselves. Except for charity, there was no relief from sickness, want and unemployment. Injured workers were at the mercy of their employers unless they could afford to sue in the courts.

The city's founders were ardent loyalists bound by British customs and traditions. Citizens still revelled in their British citizenship. Talk of an independent Canada could provoke an angry reaction. Indeed, when the Canadian Club decorated its meeting place with Canadian Ensign flags in 1903, some members regarded it as an insult to Britain - and walked out to form the Empire Club.

The newspaper Mr. Atkinson began to publish in 1899 quickly reflected his ideas. Advertising was moved off the front page. News was displayed under bold, catchy headlines. For the serious reader, there were stories about politics and the Boer War. For others, there were crime stories like "The Man She Loved Left Her To Drown." The women's pages, edited by his wife, Elmina Atkinson, offered advice to the lovelorn. The editorial page began to speak with a firm liberal conviction.

Mr. Atkinson knew he must attract new readers to succeed. To do so he offered a steady stream of prizes, contests and promotions. A 1901 promotion offering sickness and accident insurance to readers who clipped a coupon from the paper candidly said: "The Star has no apology to offer in presenting this insurance plan to the public. The object is to place the paper in the homes of 30,000 people within the next year."

The lively paper soon gained new readers. By 1907 Mr. Atkinson was able to say that, "for some months, The Star had more subscribers in the city and province than any other Toronto newspaper." One by one, most of his competitors disappeared until today the only survivors are The Star and The Globe, which merged with The Mail and Empire.

A front page statement in 1934 acknowledged that the popular appeal of the paper was the "chief implement" of its growth. But, it added, "popular appeal had little to do with that other achievement of which The Star and its readers are both aware. That achievement is the recognition at home and abroad of The Star as one of the important and purposeful newspapers of the world.

"That recognition," it said, "has come, not merely from the enterprise and energy displayed by The Star in maintaining its own correspondents abroad, nor from its sending to all important events and places special reporters to observe and describe matters of world interest.

"But because The Star, from its earliest days, has been a tireless, unremitting, propagandist in that field of the larger politics in which is determined the slow advance of human kind out of misery into happiness, out of oppression into justice, The Star's ideal being the lessening of privilege of any class and practical, applied liberalism of a fairer and free distribution of the good things in life so abundantly available in the modern world."

Mr. Atkinson's strengths were his foresight and conviction. He did not claim to be an intellectual. He learned from his experiences and reading. He recognized that Canada could not escape the social changes taking place in Britain, and, unlike his competitors, he welcomed them.

Many of the ideas were borrowed from Britain. When prime minister Lloyd George first proposed sickness and unemployment insurance, the front page of The Star proclaimed:

"DOMESTICS, CLERKS, FACTORY GIRLS, ALL TO BE INSURED - EVEN THE OFFICE BOY AND GOLF CADDIES WILL COME UNDER THIS UNEMPLOYMENT AND SICKNESS SCHEME - WILL AID WOMAN WHO BECOMES A WIDOW."

This set a pattern The Star would follow for years to come in educating the public to the need for social legislation in Canada. The crusading style of journalism that would mark The Star began within weeks of Mr. Atkinson's arrival. He saw a great future for Toronto - a city of 6,000,000 by Year 2000 - and the need to plan its future. When fire destroyed buildings along Richmond St., he saw an opportunity to create a public square in front of the city hall. With front page stories, editorials and half-page drawings, he urged the city to acquire the land.

"This is going to be a great city," the paper declared. "We should begin to shape things accordingly. If the opportunity is let slip, it may not come again until another and wiser generation, at a highly multiplied cost, procures the land and creates a square that we could now create for a song." He was right. We did not get a civic square until 1965 - at a highly multiplied price.

The Star went on to emphasize the importance of city planning, the creation of large parks and wider streets. In 1922 it advocated the widening of upper Yonge St. and Bloor St. "If city fathers had enough imagination to project their minds into the future," the paper said, "and view narrow Bloor St. as the Greater Toronto of tomorrow would view it, they would not hesitate for a moment about going on with the widening while it is yet possible to do so. Bloor St. should be widened from limit to limit . . . "

City planning was still a novel idea and would not be adopted until 1930. It finally came as a result of a grandiose plan proposed by The Star for the redevelopment of downtown Toronto which caused heated debate and controversy. The Telegram and Globe hotly opposed the idea, hinting that it was intended to enhance the value of The Star's King St. property. The redevelopment plan was defeated in a referendum, but city council then moved to establish a planning board.

Mr. Atkinson's interest in public ownership never flagged. He believed that all public monopoly services - street railway, gas, power, national airlines and even telephones - should be owned by the public. He conceded that private owners may be more efficient but argued "the fruits of the economy are garnered for the benefit of the private company."

He first campaigned for public ownership of the gas company which was approved in an election but never carried out. He was more successful in urging the city to acquire the street railway - the Toronto Transit Commission today - and the creation of Ontario Hydro.

As early as 1902 he saw the important role hydro would play in the future. "If there is anything whatever that should be under public control," the paper said, "it is the power by which the wheels of our industry are driven. What we want is the cheapest light and power which can be produced. We will not get it if we allow the intervention of private interests. We must not let private capital set up a toll gate."

To Mr. Atkinson, the real test of a great city was not its size "but whether it is a better place to live than the little city of 1834; better, that is, not only for a favoured few, but for the masses of people and especially for the more unfortunate of the masses. Has the 'underdog' a better chance now than a hundred years ago? . . . Has the gap between the rich and poor closed or widened? . . . Is the city a true 'neighbour' to its least fortunate inhabitants?"

The plight of the least fortunate, especially undernourished children, would concern Mr. Atkinson throughout his life. In 1906 he established The Star Santa Fund for needy children. He conducted food drives for the unemployed. He believed that "the greatest single cause of poverty is low wages. . . . The greatest single social reform would be to raise the wages of the worst paid workers."

He remembered his widowed mother's struggle to feed her children and advocated mother's allowance. He bluntly stated there was poverty in the city when the community refused to recognize it. He would go on to advocate the social benefits we now take for granted.

Unemployment was a deeply ingrained problem when Mr. Atkinson came to The Star. Many companies, even the city, used contract labour to escape the blame for low wages and layoffs. When jobs were completed, workers were left without employment.

He first urged the city to provide jobs cleaning up the parks and city. Then, in 1914, he began his long campaign for unemployment insurance that continued until 1941.

Pointing to Britain, the paper said the problem "ought not be dealt with in a haphazard way. It ought to be dealt with in a scientific way, in such a manner that acute and widespread distress through unemployment is impossible. This can be done. Great Britain does provide, by law, insurance against evils due to unemployment . . . The sound principle is that industry shall carry its workmen over slack times just as it carries its buildings and its machinery, and its cost of management, all its overhead charges, even in slack times.

"Business has no right to use workmen when times are good and work is plentiful and cast them aside when work is scarce and times are bad. Even the slave-holders did better than that. Industry ought in good times lay aside part of its profits as a fund for providing for workmen in slack times. Let us attack the problem."

The Star established itself as a friend of workers in 1903 with an editorial stating "workers have a natural right to strike and to ask for more and quit if they do not get it. Why upbraid them and say they are blocking the growth of the city and, therefore, are bad citizens? Do we say the manufacturer must never ask higher prices for his goods, or if he does, that he is an industry wrecker? . . . Shall the owners of houses that raise rents, and occupants of those houses, be called hard names because they seek to raise their wages?"

He first proposed workmen's compensation in 1900 and hounded the Ontario government until it was adopted over business opposition in 1915. Similarly, he campaigned for minimum wages from 1909 until they became law in 1937.

The adoption of old age pensions in Britain prompted him to call for a similar plan in Canada. "It is simple mockery," the paper said in 1907, "to tell the unskilled worker that he ought to put by enough to make himself comfortable in his declining years. He could only do so, if at all, by adopting a standard of living so low as very seriously to lower the plane of civilization."

The Star's strong support for unions and collective bargaining was put to a severe test by the Winnipeg General Strike in 1919, which led to fears Communists were trying to overthrow the government. Federal government investigators initially blamed Bolshevists for the strike. Mr. Atkinson was not convinced. He sent two senior reporters to Winnipeg to investigate. They found the principal cause was the refusal of employers to negotiate. A subsequent government commission confirmed this finding.

Another major confrontation came in 1937 with the General Motors strike at Oshawa. The issue here was the right of workers to be represented by an international union. Premier Mitch Hepburn intervened on the side of the company, recruiting a special police force to keep "foreign agitators" out of Canada. The Star calmly supported the workers, stating, "If capital is international in its operations, labour must be free to take the same course." General Motors promptly cancelled its advertising.

Mr. Atkinson was not fazed. Earlier Eaton's had temporarily withdrawn its advertising. He believed that a newspaper should reflect the interests and concerns of is readers. "A newspaper carries advertising, but would not do so except for its readers."

Oddly enough, when his editorial employees first organized a union, he declined to negotiate, insisting that the union also organize the Telegram and Globe staff as the printers and pressmen had done.

The union originally promised in a letter to do so, but later withdrew this undertaking. Eventually, the newspaper guild did organize Star employees.

Mr. Atkinson was a Canadian nationalist who believed strongly in Canadian independence. Canada had attained self-government with Confederation in 1867, but Britain still retained the power to disallow legislation. Canada was bound by British treaties and lacked the authority to negotiate even with the United States.

Mr. Atkinson acknowledged ties with Britain afforded protection against American annexation, but he questioned whether Canada could achieve its full potential unless it became an equal partner with Britain in what is now the Commonwealth of free nations.

His vision of an independent Canada clashed with the influential Orange Lodge and others who prided themselves in their British citizenship. He persisted in the face of strong opposition to promote pride in Canada and Canadian institutions.

Canadian judges, the paper said, are not "ignoramuses." Appeals to the British privy council should end. Canada, not Britain, should appoint the governor-general. Hereditary titles should cease. Canada should adopt a Maple Leaf flag. The Canadian Constitution should be repatriated to Canada. Children born in Canada should be registered as Canadian citizens. Eventually, all these things happened.

Mr. Atkinson saw nationalism as a means "to unite the various parts of the country. We need a spirit that will unite native-born Canadians of British or French descent, newly arrived immigrants from the British Isles, from the United States, from Russia, from every part of the world. . . . If Canada is to be united and strong, it must have a national spirit as powerful as that which pervades the United States."

To foster better relations with Quebec, the paper proposed that members of Quebec's 65th Regiment be invited to Toronto to celebrate Queen Victoria's birthday. "If they came to Toronto and saw the city, met our people, were greeted with applause with their presence, their appearance, the sentiment of the occasion would inevitably inspire; every man in the ranks would return home knowing something of the cordial goodwill that the great mass of Ontario people have for their fellow countrymen of Quebec."

The paper went on to advocate what today is bilingualism. "The fact that French is the language of a large section of the people of Canada certainly establishes a reason why all Canadians should understand French as well as English." Of course, it added, "there can be no compulsion."

Mr. Atkinson's relations with business friends were strained and he frequently ate lunch alone at the National Club. One reason was his support for unions. Another was his insistence that the cost of social benefits should "fall most heavily - as indeed it should - upon moneyed men and corporations."

Mr. Atkinson was frequently accused of being a socialist, if not a Communist. He was neither. He saw defects in the capitalist system but acknowledged in an editorial that it was "the best industrial system yet devised."

The chief defect, he saw, was that it "created poverty in the midst of plenty." He would go on say that "the regulation of profits is, in time, likely to be regarded as the only means by which a country can protect the interests of its population. So long as there is no limit on profits that one can make in business, no fairer general scheme of life can be worked out."

Wealth, in Mr. Atkinson's opinion was not earned and should be taxed. It is "amassed, accumulated, collected, gathered, taken - there are many words to describe the process but 'earned' is not one of them. If a man were operating alone in the world, he could not possibly get himself the things which a wealthy man is about to enjoy. He enjoys them because they have been provided for him by a vast number of people, by the primary producers who have worked under and on the earth; by the men who have transported and processed the primary products, and by all other toiling human beings who have brought the wealth to the rich man's door.

"Under our present social system, there is nothing wrong with his being rich so long as he make the right use of his riches. But there is nothing wrong, either, about the government taking a substantial part of his riches away to make good use of them on behalf of the masses of people from whom they have been collected."

Mr. Atkinson's wide-ranging interests extended to free speech, racial discrimination and minority rights. Toronto in the early 1900s was not a hospitable place for Jews, Catholics and foreign-born immigrants. He defended Jews in editorials and published feature stories and pictures about Catholics on the front page.

He supported the right of socialists to hold street meetings in 1908 and, almost alone, defended the right of Communists to hold meetings in Queen's Park in the early 1930s. Police then were attempting to break up the meetings with the backing of The Globe and Telegram. When University of Toronto professors finally issued a statement affirming their belief "in the free expression of opinion, however unpopular or erroneous," the Board of Trade demanded that they be fired.

"There is a misunderstanding," The Star said, "that, if anybody openly desired to preserve the British and democratic institution of free speech, he must necessarily be a Communist himself or in favour of communism or sympathetic with it. The very opposite is the case. Nobody who believes in free speech can believe in communism for, as it is applied, it absolutely suppresses free speech."

Mr. Atkinson did not live to see the adoption of health insurance. But he was one of its architects. He was chairman of a subcommittee at a Liberal party conference in 1915 that recommended the government adopt old age and mother's pensions and national insurance against sickness and unemployment as soon as possible